The following explanation and illustrations are an excerpt from CMEGroup’s publication, “Self-Study Guide to Hedging with Grain and Oilseed Futures and Options”. As an educational supplement, watch an example using a simple online hedge calculator in our newsletter. Take a quiz to help further your knowledge.

Basis: The Link Between Cash and Futures prices

All of the examples just presented assumed identical cash and futures prices. But, if you are in a business that involves buying or selling grain or oilseeds, you know the cash price in your area or what your supplier quotes for a given commodity usually differs from the price quoted in the futures market. Basically, the local cash price for a commodity is the futures price adjusted for such variables as freight, handling, storage and quality, as well as the local supply and demand factors. The price difference between the cash and futures prices may be slight or it may be substantial, and the two prices may not always vary by the same amount.

This price difference (cash price – futures price) is known as the basis.

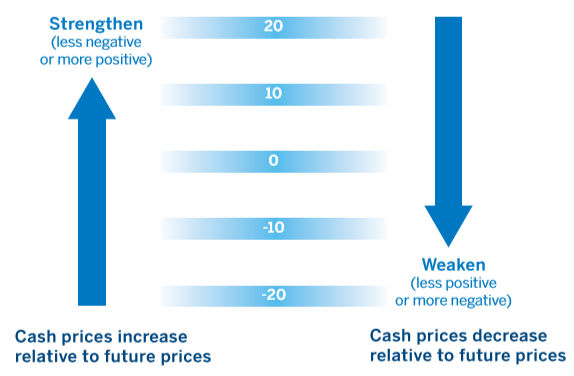

A primary consideration in evaluating the basis is its potential to strengthen or weaken. The more positive (or less negative) the basis becomes, the stronger it is. In contrast, the more negative (or less positive) the basis becomes, the weaker it is.

For example, a basis change from 50 cents under (a cash price 50 cents less than the futures price) to a basis of 40 cents under (a cash price 40 cents less than the futures price) indicates a strengthening basis, even though the basis is still negative. On the other hand, a basis change from 20 cents over (a cash price 20 cents more than the futures price) to a basis of 15 cents over (a cash price 15 cents more than the futures price) indicates a weakening basis, despite the fact that the basis is still positive. (Note: Within the grain industry a basis of 15 cents over or 15 cents under a given futures contract is usually referred to as “15 over” or “15 under.” The word “cents” is dropped.) Basis is simply quoting the relationship of the local cash price to the futures price.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Basis and the Short Hedger

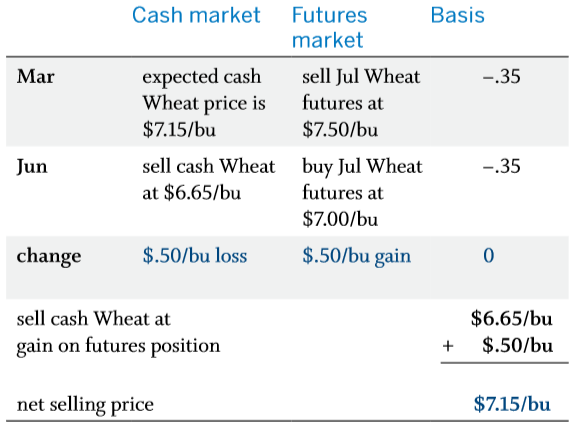

Basis is important to the hedger because it affects the final outcome of a hedge. For example, suppose it is March and you plan to sell wheat to your local elevator in mid-June. The July Wheat futures price is $7.50 per bushel, and the cash price in your area in mid-June is normally about 35 under the July futures price.

The approximate price you can establish by hedging is $7.15 per bushel ($7.50 – $.35) provided the basis is 35 under. The previous table shows the results if the futures price declines to $7.00 by June and the basis is 35 under.

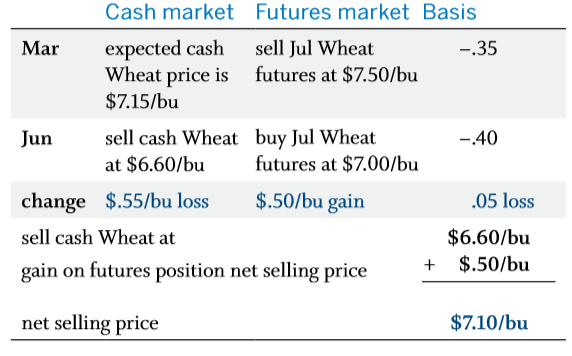

Suppose, instead, the basis in mid-June had turned out to be 40 under rather than the expected 35 under. Then the net selling price would be $7.10, rather than $7.15.

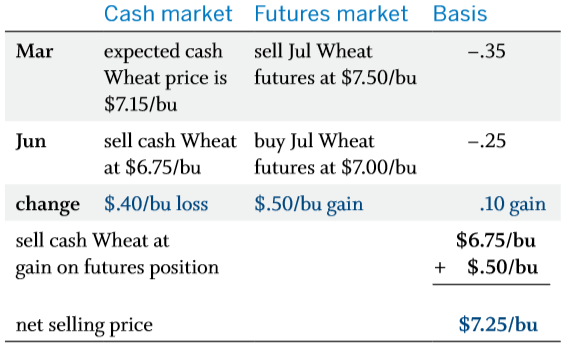

This example illustrates how a weaker-than-expected basis reduces your net selling price. And, as you might expect, your net selling price increases with a stronger-than-expected basis. Look at the following example.

As explained earlier, a short hedger benefits from a strengthening basis. This information is important to consider when hedging. That is, as a short hedger, if you like the current futures price and expect the basis to strengthen, you should consider hedging a portion of your crop or inventory as shown in the next table. On the other hand, if you expect the basis to weaken and would benefit from today’s prices, you might consider selling your commodity now.

Basis and the Long Hedger

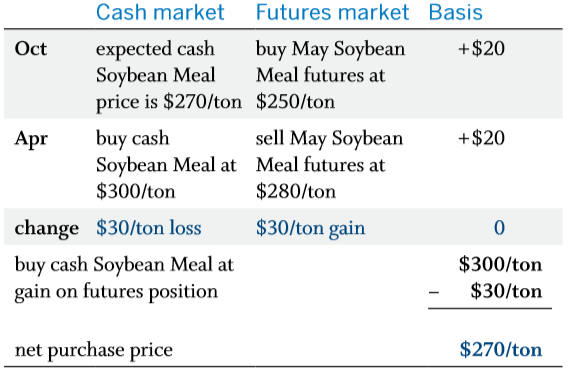

How does basis affect the performance of a long hedge? Let’s look first at a livestock feeder who in October is planning to buy soybean meal in April. May Soybean Meal futures are $250 per ton and the local basis in April is typically $20 over the May futures price, for an expected purchase price of $270 per ton ($250 + $20). If the futures price increases to $280 by April and the basis is $20 over, the net purchase price remains at $270 per ton.

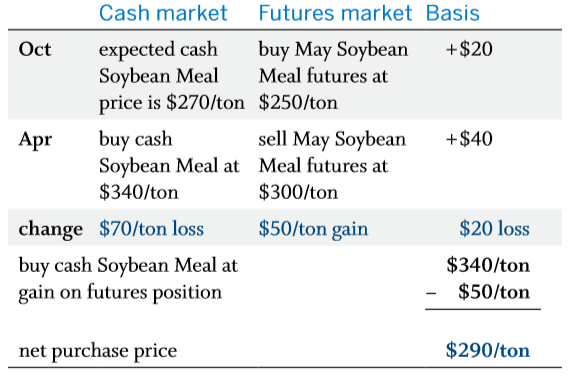

What if the basis strengthens – in this case, more positive – and instead of the expected $20 per ton over, it is actually $40 per ton over in April? Then the net purchase price increases by $20 to $290.

Conversely, if the basis weakens, moving from $20 over to $10 over, the net purchase price drops to $260 per ton ($250 + $10).

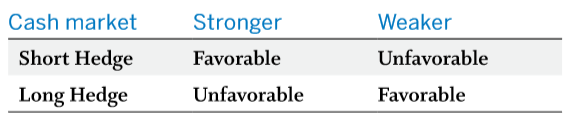

Notice how long hedgers benefit from a weakening basis – just the opposite of a short hedger. What is important to consider when hedging is basis history and market expectations. As a long hedger, if you like the current futures price and expect the basis to weaken, you should consider hedging a portion of your commodity purchase. On the other hand, if you expect the basis to strengthen and like today’s prices, you might consider buying or pricing your commodity now.

Hedging with futures offers you the opportunity to establish an approximate price months in advance of the actual sale or purchase and protects the hedger from unfavorable price changes. This is possible because cash and futures prices tend to move in the same direction and by similar amounts, so losses in one market can be offset with gains in the other. Although the futures hedger is unable to benefit from favorable price changes, you are protected from unfavorable market moves.

Basis risk is considerably less than price risk, but basis behavior can have a significant impact on the performance of a hedge. A stronger-than-expected basis will benefit a short hedger, while a weaker-than-expected basis works to the advantage of a long hedger.

If you're a commodity risk manager looking for assistance on hedging, please visit our partner site OahuCapital.com for active assistance.