The following explanation and illustrations are an excerpt from CMEGroup’s publication, “Self-Study Guide to Hedging with Grain and Oilseed Futures and Options”. As an educational supplement, watch an example using a simple online hedge calculator in our newsletter. Take a quiz to help further your knowledge.

Buying Futures for protection against rising prices

Assume you are a feed manufacturer and purchase corn on a regular basis. It is December and you are in the process of planning your corn purchases for the month of April – wanting to take delivery of the corn during mid-April. Several suppliers in the area are offering long-term purchase agreements, with the best quote among them of 5 cents over May futures. CME Group May futures are currently trading at $4.75 per bushel, equating to a cash forward offer of $4.80 per bushel.

If you take the long-term purchase agreement, you will lock in the futures price of $4.75 per bushel and a basis of 5 cents over, or a flat price of $4.80 per bushel. Or, you could establish a futures hedge, locking in a futures price of $4.75 per bushel but leaving the basis open.

In reviewing your records and historical prices, you discover the spot price of corn in your area during mid-April averages 5 cents under the May futures price. And, based on current market conditions and what you anticipate happening between now and April, you believe the mid-April basis will be close to 5 cents under.

Action

Since you like the current futures price but anticipate the basis weakening, you decide to hedge your purchase using futures rather than entering into a long-term purchase agreement. You purchase the number of corn contracts equal to the amount of corn you want to hedge. For example, if you want to hedge 15,000 bushels of corn, you buy (go “long”) three Corn futures contracts because each contract equals 5,000 bushels.

By hedging with May Corn futures, you lock in a purchase price level of $4.75 but the basis level is not locked in at this time. If the basis weakens by April, you will benefit from any basis improvement. Of course, you realize the basis could surprise you and strengthen, but, based on your records and market expectations, you feel it is in your best interest to hedge your purchases.

Prices Increase Scenario

If the price increases and the basis at 5 cents over, you will purchase corn at $4.80 per bushel (futures price of $4.75 + the basis of $.05 over). But if the price increases and the basis weakens, the purchase price is reduced accordingly.

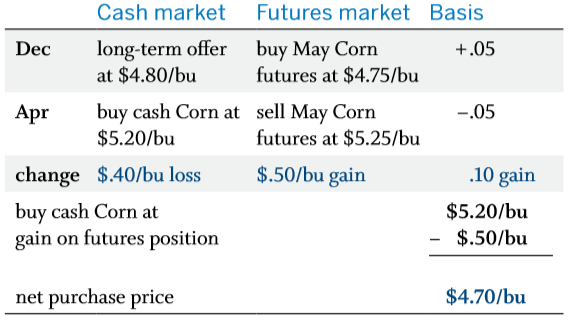

Assume by mid-April, when you need to purchase the physical corn, the May futures price has increased to $5.25 and the best offer for physical corn in your area is $5.20 per bushel (futures price – the basis of $.05 under).

With the futures price at $5.25, the May Corn futures contract is sold back for a net gain of 50 cents per bushel ($5.25 – $4.75). That amount is deducted from the current local cash price of corn, $5.20 per bushel, which equals a net purchase price of $4.70. Notice the price is 50 cents lower than the current cash price and 10 cents lower than what you would have paid for corn through a long-term purchase agreement. The lower price is a result of a weakening of the basis by 10 cents, moving from 5 cents over to 5 cents under May futures.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Prices Decrease Scenario

If prices decrease and the basis remains unchanged, you will still pay $4.80 per bushel for corn. Hedging with futures provides protection against rising prices, but it does not allow you to take advantage of lower prices. In making the decision to hedge, one is willing to give up the chance to take advantage of lower prices in return for price protection. On the other hand, the purchase price will be lower if the basis weakens.

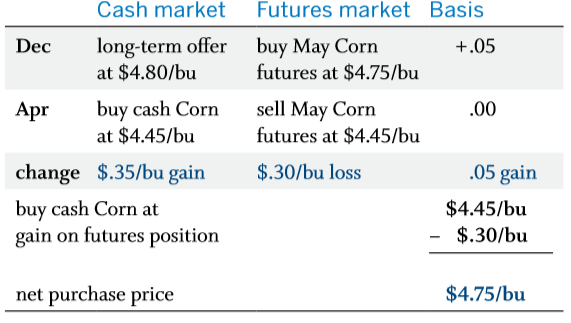

Assume by mid-April the May futures price is $4.45 per bushel and the best quote offered by an area supplier is also $4.45 per bushel. You purchase corn from the supplier and simultaneously offset your futures position by selling back the futures contracts you initially bought.

Even though you were able to purchase cash corn at a lower price, you lost 30 cents on your futures position. This equates to a net purchase price for corn of $4.75. The purchase price is still 5 cents lower than what you would have paid for corn through a long-term purchase agreement. Again, this difference reflects a weakening of the basis from 5 cents over to even (no basis).

In hindsight, you would have been better off neither taking the long-term purchase agreement nor hedging because prices fell. But your job is to purchase corn, add value to it, and sell the final product at a profit. If you don’t do anything to manage price risk, the result could be disastrous to your firm’s bottom line. Back in December, you evaluated the price of corn, basis records and your firm’s expected profits based upon that information. You determined by hedging and locking in the price for corn your firm could earn a profit. You also believed the basis would weaken, so you hedged to try and take advantage of a weakening basis. Therefore, you accomplished what you intended. The price of corn could have increased just as easily.

Prices Increase/Basis Strengthens Scenario

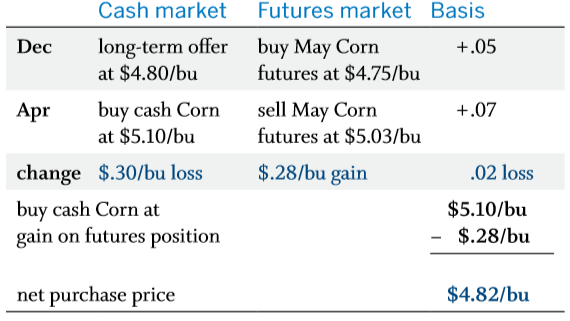

If the price rises and the basis strengthens, you will be protected from the price increase by hedging but the strengthening basis will increase the final net purchase price relative to the long-term purchase agreement.

Assume in mid-April your supplier is offering corn at $5.10 per bushel and the May futures contract is trading at $5.03 per bushel. You purchase the physical corn and offset your futures position by selling back your futures contracts at $5.03. This provides you with a futures gain of 28 cents per bushel, which lowers the net purchase price. However, the gain does not make up entirely for the higher price of corn. The 2-cent difference between the long-term purchase agreement and the net purchase price reflects the strengthening basis.

As we’ve seen in the preceding examples, the final outcome of a futures hedge depends on what happens to basis between the time a hedge is initiated and offset. In those scenarios, you benefited from a weakening basis.

In regard to other marketing alternatives, you may be asking yourself how does futures hedging compare? Suppose you had entered a long-term purchase agreement instead of hedging? Or maybe you did nothing at all – what happens then?

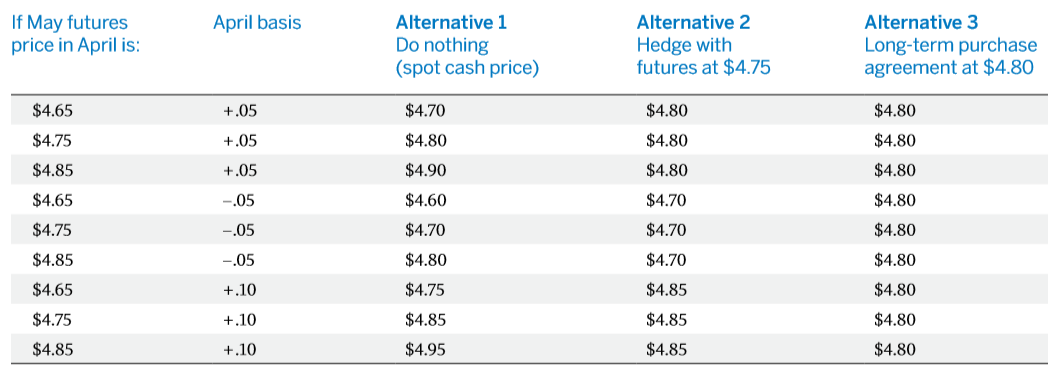

The table below compares your alternatives illustrating the potential net purchase price under several possible futures prices and basis scenarios. You initially bought May Corn futures at $4.75.

You cannot predict the future but you can manage it. By evaluating your market expectations for the months ahead and reviewing past records, you will be in a better position to take action and not let a buying opportunity pass you by.

Alternative 1 shows what your purchase price would be if you did nothing at all. While you would benefit from a price decrease, you are at risk if prices increase and you are unable to manage your bottom line.

Alternative 2 shows what your purchase price would be if you established a long hedge in December, offsetting the futures position when you purchase physical corn in April. As you can see, a changing basis affects the net purchase price but not as much as a significant price change.

Alternative 3 shows what your purchase price would be if you entered a long-term purchase agreement in December. Basically, nothing affected your final purchase price but you could not take advantage of a weakening basis or lower prices.

Selling Futures for Protection Against Falling Prices

Assume you are a corn producer. It is May 15 and you just finished planting your crop. The weather has been unseasonably dry, driving prices up significantly. However, you feel the weather pattern is temporary and are concerned corn prices will decline before harvest.

Currently, Dec Corn futures are trading at $4.70 per bushel and the best bid on a forward contract is $4.45 per bushel, or 25 cents under the December futures contract. Your estimated cost of production is $4.10 per bushel. Therefore, you could lock in a profit of 35 cents per bushel through this forward contract. Before entering into the contract, you review historical prices and basis records and discover the local basis during mid-November is usually about 15 cents under December futures.

Action

Because the basis in the forward contract is historically weak, you decide to hedge using futures. You sell the number of corn contracts equal to the amount of corn you want to hedge. For example, if you want to hedge 20,000 bushels of corn, you sell (go “short”) four Corn futures contracts because each futures contract equals 5,000 bushels. By selling Dec Corn futures, you lock in a selling price of $4.45 if the basis remains unchanged (futures price of $4.70 – the basis of $.25). If the basis strengthens, you will benefit from any basis appreciation. But remember, there is a chance the basis could actually weaken. So, although you maintain the basis risk, basis is generally much more stable and predictable than either the cash market or futures market prices.

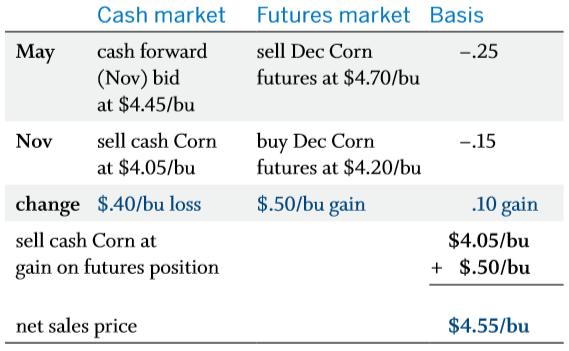

Prices Decrease Scenario

If the price declines and the basis remains unchanged, you are protected from the price decline and will receive $4.45 per bushel for your crop (futures price of $4.70 – the basis of $.25). If the price drops and the basis strengthens, you will receive a higher than expected price for your corn. By November, the best spot bid in your area for corn is $4.05 per bushel. Fortunately, you were hedged in the futures market and the current December futures price is $4.20. When you offset the futures position by buying back the same type and amount of futures contracts as you initially sold, you realize a gain of 50 cents per bushel ($4.70 – $4.20). Your gain in the futures market increases your net sales price. As you can see from the following table, the net sales price is actually 10 cents greater than the forward contract bid quoted in May. This price difference reflects the change in basis, which strengthened by 10 cents between May and November.

Prices Increase Scenario

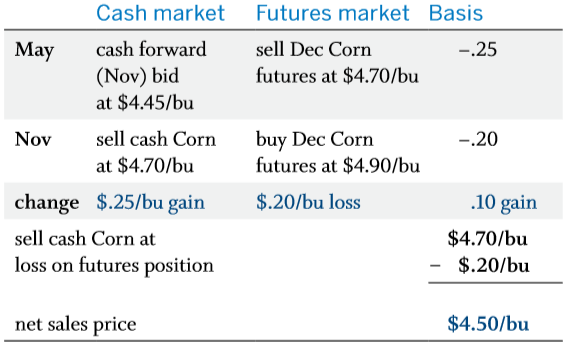

If the price increases and the basis remains unchanged, you will still receive $4.45 per bushel for your crop. That is the futures price ($4.70) less the basis (25 cents under). With futures hedging, you lock in a selling price and cannot take advantage of a price increase. The only variable that ultimately affects your selling price is basis. As shown in the following example, you will receive a higher than expected price for your corn if the basis strengthens.

Suppose by mid-November the futures price increased to $4.90 per bushel and the local price for corn is $4.70 per bushel. Under this scenario, you will receive $4.50 per bushel – 5 cents more than the May forward contract bid. In reviewing the table below, you will see the relatively higher price reflects a strengthening basis and is not the result of a price level increase. Once you establish a hedge, the futures price level is locked in. The only variable is basis.

If you could have predicted the future in May, more than likely you would have waited and sold your corn in November for $4.70 per bushel rather than hedging. But predicting the future is beyond your control. In May, you liked the price level and knew the basis was historically weak. Knowing your production cost was $4.10 per bushel, a selling price of $4.45 provided you a respectable profit margin.

In both of these examples, the basis strengthened between the time the hedge was initiated and offset, which worked to your advantage. But how would your net selling price be affected if the basis weakened?

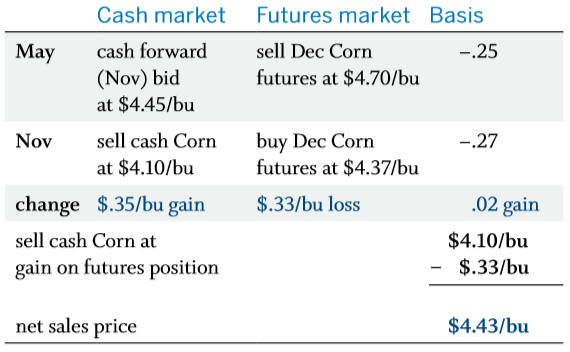

Prices Decrease/Basis Weakens Scenario

If the price falls and the basis weakens, you will be protected from the price decrease by hedging but the weakening basis will slightly decrease the final net sales price.

Assume by mid-November, the December futures price is $4.37 and the local basis is 27 cents under. After offsetting your futures position and simultaneously selling your corn, the net sales price equals $4.43 per bushel. You will notice the net sales price is 2 cents lower than the forward contract bid in May, reflecting the weaker basis.

As we’ve seen in the preceding examples, the final outcome of a futures hedge depends on what happens to the basis between the time a hedge is initiated and offset. In these scenarios, you benefited from a strengthening basis and received a lower selling price from a weakening basis.

In regard to other marketing alternatives, you may be asking yourself how does futures hedging compare? Suppose you had entered a forward contract instead of hedging? Or maybe you did nothing – what happens then?

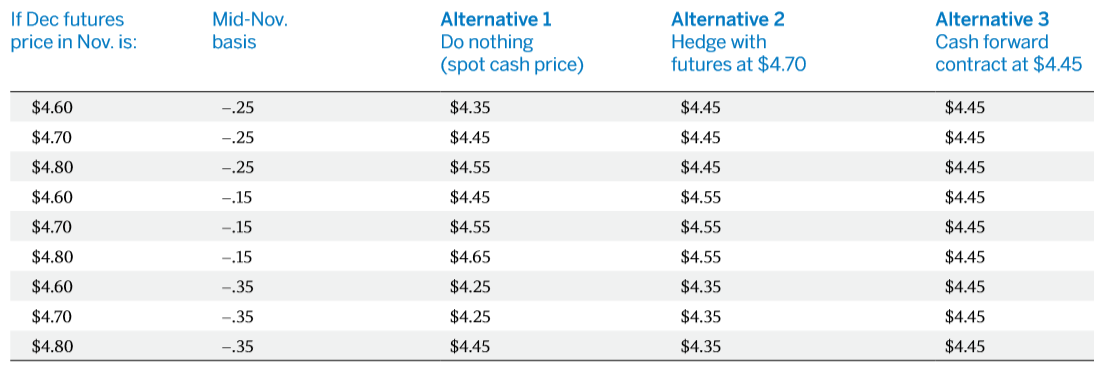

The following table compares your alternatives and illustrates the potential net return under several different price levels and changes to the basis.

You can calculate your net sales price under different futures prices and changes to the basis. Of course, hindsight is always 20/20 but historical records will help you take action and not let a selling opportunity pass you up.

Alternative 1 shows what your net sales price would be if you did nothing at all. While you would benefit from a price increase, you are at risk if the price of corn decreases and at the mercy of the market.

Alternative 2 shows what your net return would be if you established a short hedge at $4.70 in May, offsetting the futures position when you sell your corn in November. As you can see, a changing basis is the only thing that affects the net sales price.

Alternative 3 shows what your net return would be if you cash forward contracted in May. Basically, nothing affected your final sales price, but you could not take advantage of a strengthening basis or higher prices.

The following table compares your alternatives and illustrates the potential net return under several different price levels and changes to the basis.

If you're a commodity risk manager looking for assistance on hedging, please visit our partner site OahuCapital.com for active assistance.